ALTs expectations high school junior high school SHS teaching

by sendaiben

leave a comment

Updating the ALT Playbook

A list of dos and don’ts for ALTs and other language teachers

I read Baye McNeill’s excellent book Loco in Yokohama a few weeks ago, and thoroughly enjoyed it. It’s a great read and it took me right back to my days teaching in junior high school as a first- and second-year ALT on the JET Programme.

It also reminded me of what I used to do in the classroom back then.

Like many ALTs, I came to Japan with little teaching experience (I had taught a couple of classes and done some tutoring in China). I received minimal training and very little supervision from my colleagues and supervisors, both in the school and in the local board of education. I got a lot of advice from other ALTs and just muddled through.

Thinking back now I can think of many ways I could have been more effective and served my students better. Don’t get me wrong, I think I did my best with the information I had and made a positive contribution, but I could have done so much more.

Here is my advice to ALTs and language teachers in Japanese junior and senior high schools:

- DO think about your goals for the year, the month, and the class. Lesson planning should end with the language target and textbook page, not start there. Try to link lessons together so that students can review and preview past and future activities and language.

- DON’T worry about things being fun. Video games are fun. Hanging out with your friends is fun. Language classes are seldom fun. Instead of fun, think about challenging, achievable, and meaningful. Success is the most motivating experience for students, and many of them are turned off by classes in which they never experience success. Give them that, and they will enjoy the class much more than if they had done some ‘fun’ activities. I haven’t seen many math classes here in Japan revolving around games, so why should language classes?

- DO think about time on task. Many classroom activities involve just one or two students, while all the others just watch or get bored. Games like pass the parcel, criss cross, and relay games were staples in my classroom, but I now believe that having students ask and answer simple questions in pairs for a couple of minutes would have been a much more useful activity. I bet many of the students would have enjoyed it more too.

- DON’T talk too much. I believe students need to use the language to acquire it, which in any class bigger than five students or so means doing pair or small group activities. Make sure there is a healthy balance of teacher talking time and student talking time in your class.

- DO set homework and encourage students to practice outside of class. Self-study using printed, audio, or online materials is the only realistic way for students to get good at English. Model appropriate activities in class and follow up to see what students are doing. Take an interest in the students who are practicing and keep nagging the ones that don’t.

- DON’T give up. I haven’t met a single student who doesn’t secretly want to be good at English. Keep giving them the chance to have a bit of success, to find something interesting to do in or with English, and you might be able to change their future relationship with the language.

What do you think of the list? Anything to add or disagree with?

Review: Question Quest The Language Card Game

We’ve been trying out Question Quest for the last few weeks at Cambridge English.

We love AGO, the UNO-like simple English question game, and David Lisgo’s Switchit card games.

When I saw Question Quest’s website I was extremely interested. It seemed like it would appeal to our teenage learners and complement our existing card games so I ordered a copy immediately.

Once it arrived I was impressed with the production values. The game is very attractive, with incredible artwork, quality materials, and a sturdy box.

The good

- The artwork is beautiful and very appealing to Japanese teenagers

- The game includes English and Japanese instructions

- The materials are high-quality and pretty sturdy

- The language covered is very appropriate for our students

- Cards include example sentences to help students

- The gameplay is interesting and more skilled players are more likely to win

- Students practice strategies such as asking for more information, asking a third party, and expressing their lack of understanding

- Reasonably priced (1575 yen for over 100 cards)

The bad

- The game as written takes a long time to play (probably 20-40 minutes), which was a bit long for us

- It took a while for us to understand the rules, both teachers and students

- Some of the example questions on the cards are a bit unintuitive

Overall

This is a very promising resource. We normally do some kind of game or activity in the last 5-10 minutes of class, so found that Question Quest did not quite fit in that time. However, we were able to adapt the game (teacher asks the questions to students, playing without the conversation strategy cards, etc.) to fit the shorter time.

We also took some time and played some full games. Lots of fun and the students are practicing useful conversational gambits.

Overall I recommend Question Quest to teachers of teenage or young adult students (although it would certainly work with the right group of adults too). It’s an attractive and versatile resource. A single pack is a very reasonable investment for a small classroom: teachers with larger classes would need one set for each group of up to 4-6 players.

Has anyone else tried this game?

eikaiwa expectations high school JHS junior high school kids Language learning teaching vocabulary

by sendaiben

14 comments

My ‘almost’ mini-lesson

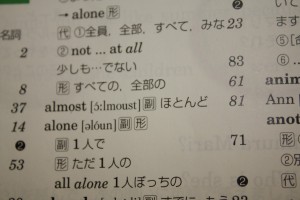

Unfortunately, many students in Japan are taught that ‘almost’ in English is ‘hotondo’ in Japanese

Sadly this is not true, so over the years I have developed a short mini-lesson to correct this false impression and help students better understand the meaning of almost.

The lesson can start at any time, but it requires a trigger: one of the students must translate almost as hotondo.

Once that happens, I quickly go through the following steps:

- I point out that even though many teachers and textbooks teach this, almost is not the same as hotondo

- I pretend to trip, and then say “phew, I almost fell over just now”

- I ask the students to translate the previous sentence: “hotondo korobimashita” sounds really strange, so clearly hotondo is not a good translation here

- I tell the students I planned to go to Tokyo this morning, but ended up not going. “I almost went to Tokyo”

- “Hotondo Tokyo ni ikimashita” also sounds weird

- I offer two alternative translations for almost: mou chotto de ~ and ~wo suru tokoro datta

- I explain that hotondo is actually almost all in English: mou chotto de zenbu

Of course, this illustrates vividly the perils of learning and teaching vocabulary out of context, which provides another excellent mini-lesson for the students 🙂

Do you have any favourite mini-lessons?

business curriculum eikaiwa ES expectations JHS junior high school kids language courses Language learning overseas study trips school management summer camp young learners

by sendaiben

2 comments

Taking students to summer camp in the US

This is a guest post (the first on this blog!) by a friend of mine, Ryan Hagglund. He has an extremely promising variation on the usual study abroad trip that I thought you would find interesting. Enjoy and let us know what you think in the comments.

After many years of thinking about it, we finally took students from our school (MY English School in Yamagata) to the US for the first time this summer. Thanks to all the advice and stories I read and heard from others, the trip was overall a success and will hopefully serve as a building block for many more to come.

My impression is that most international trips English schools organize involve some form of formal study. While there is obviously nothing wrong with studying—we ARE a language school—it seems like there’s plenty of time for the students to study while in Japan. The main purpose for us in going was to give the students something they couldn’t receive here: the opportunity to interact with large numbers of English-speaking children of their own age. We wanted to give them an experience that would lead to greater motivation and increased interaction skills, among other things. The instrument we chose to accomplish this was to have the children attend a summer camp intended for children who are native speakers of English, not English learners.

We chose Warm Beach Camp in Stanwood, Washington. We chose Warm Beach for several reasons. First, it is the camp I attended when an elementary and JHS student, so I was familiar with the facilities. Having attended almost 30 years ago, however, I no longer had connections to any of the staff. Second, it is a large facility that not only has many activities for campers to do, but was also able to house our staff away from our students but still onsite. Third, it gave considerable value for the price. Camp was only US $399 per student for six days and five nights—including meals—and they supplied free room and board for our staff in a separate onsite facility. They also provided free sleeping bags and pillows to our students. (Warm Beach is a Christian camp facility, but we were careful to make sure our students and their parents were aware of this. There are most likely secular camps with similar facilities and value.)

We took five students—two boys and three girls—ages 9-13 (Japanese elementary 4th grade to JHS 2nd year). There were approximately 80 campers all together ages 9-11 (US 4th to 6th grade) divided into cabins of six or seven students each. Our 13-year-old student had no problems relating to the younger campers, though JHS 1st year would probably be a good cutoff. Since none of the US campers nor counselors spoke Japanese, the students had to navigate in English. What was nice, however, were the many activities the children were able to participate in, allowing them to interact in English without consciously having to overly focus on the language itself. Some of the activities they participated in were: field games, swimming, archery, horseback riding, canoeing, wall climbing, BB-gun shooting, mini-golf, and a bonfire. While it was challenging for them at first, by the end of the trip four of the five students said they would like to stay longer. The fifth (12 years old) said she was glad to have come, but just ready to go home. We were only with the students for a daily meeting each evening, when pre-activity safety instructions in Japanese were necessary, and when a student became homesick and needed a little extra support. We had a pre-paid US cell phone so the camp and/or counselors could reach us at any time if necessary. They only called us once.

While the camp was our focus, we did do other activities as well. Our schedule was as follows:

Saturday Aug 3 – Arrive in Seattle and tour the city

Sunday Aug 4 – Visit Wild Waves Theme Park

Monday Aug 5 – Saturday Aug 10 – Attend camp and Seattle Mariners baseball game (Aug 10)

Sunday Aug 11 – Return to Japan

We will probably add an additional day of Seattle sightseeing if we go again next year.

Camp positives:

1) No need to be concerned about the quality of homestay families.

2) No need to worry about logistics for most of the trip. While at the camp, we were able to focus entirely on the students’ linguistic and emotional needs, while enjoying ourselves for most of the time. The camp took care of the rest.

3) No need to think of specific language activities, as the situation itself required meaningful English interaction from our students.

4) The camp wanted the trip to be successful as much as we did.

5) No need to pay a third party for special arrangements.

6) Students needed very little spending money. Each student brought 20,000 yen in spending money, but none of them came close to using it all.

7) Since almost everything was included in the camp price, there were fewer opportunities for financial surprises.

8) 24-hour onsite certified nurse, removing the need for us to worry about student sickness and/or injury.

Camp possible negatives:

1) We did have to plan the logistics outside of camp time. This included airline booking, three nights of hotel, sightseeing in Seattle, and transportation to and from the camp. While not difficult, might be hard to leave to a school teacher or staff member not familiar with the Seattle area.

2) Not as appropriate for students who would prefer a “travel experience” versus an “immersion experience”.

All in all, it was a very successful trip—especially for a first time. We are already working to produce marketing materials for a similar trip next year.

Ryan Hagglund is President and CEO of MY English School in Yamagata Prefecture. He has lived in Japan for 15 years and originally hails from the Pacific Northwest. He is married to Maki Hagglund and has three children: Aiden (8), Ian (6), and Sean (4).

business eikaiwa expectations high school junior high school school management study trips young learners

by sendaiben

17 comments

Taking Students to Europe (2013)

After the (semi-)successful study trip to Australia’s Gold Coast in 2012, we decided we wanted to do something similar this year.

In Australia, the best things we did were as a group, and the worst part of the trip were the host families, so this time we tried to put together a kind of eye-opening cultural tour, with a week in London and three days in Paris.

The students were interested but their parents weren’t. “Sounds like you’re just going on a trip”, they said, and weren’t open to the argument that it was the kind of trip that most kids in Japan never have the chance to make.

We quickly rethought our plans and changed the trip to incorporate a week’s homestay/English classes in London with three days in Paris. Seven students signed up, fewer than the ten we had set as a minimum. I wanted to cancel, but the school manager decided to press ahead as a learning experience.

We went with a company in the UK recommended by a friend of mine. Big mistake.

The problems

1. The school we partnered with for this trip was disorganized and unprofessional. The frequently forgot things, failed to deliver on previously agreed conditions, and three days before the trip emailed me saying “we couldn’t find the last homestay family for you, so let’s just refund your money and call it quits”. Our office manager physically collapsed when I relayed that message. I was able to broker a solution eventually, but it was incredibly stressful. After we arrived, instead of providing staff to guide us on field trips as agreed, they dropped us off at various places leaving the teacher accompanying the students to try to salvage things and provide tours and activities on the spot. Classrooms were booked at the wrong time, activities were booked on the wrong day. Scheduled activities had to be changed because they were not available on Sundays, and so on. Instead of providing classes for each level of student (we had three different levels of ability) they just provided two. None of this was said in advance, it just happened and we decided to just get through the experience without upsetting the students rather than argue.

2. Organizing everything ourselves meant dealing with airlines, hotels, transport companies, schools, museums, restaurants, etc. Once we were in country, the sole teacher on the trip had an excessive amount of responsibilities and stress. For example, on the last day we had a guided tour of Versailles including pickup from the hotel and drop off at the airport, but until the minibus actually turned up we couldn’t be sure it would happen so had to have a plan B in place. Everything turned out okay in the end (I don’t think the students noticed the problems) but it was a bit too intense.

3. Due to a last-minute venue change (from London to Cornwall!) we ended up needing to take two long (6-hour) journeys by minibus. This was a bit of a waste of time. I found out later that we could have toured London first, then made our way to Cornwall, then flown from there to Paris, which would have been a lot better.

4. There were a large number of unanticipated supplementary expenses, from meals to transport to laundry, and as the organizers we felt responsible for these.

The benefits

1. We actually had nice homestay families this time (which is 90% of the battle). Also, Cornwall is a great place and the students enjoyed getting to know it.

2. Touring London for one day and Paris for three was fantastic. The students were blown away by the buildings, the museums, and the ice cream 🙂

3. Despite the unanticipated expenses above, and not having enough students, the trip was slightly profitable.

Things we learned

1. Partnering with good people/organizations is essential. Trying to pick up the pieces after someone else drops things is exhausting and stressful, as is making contingency plans on the fly. We will be much more careful in the future.

2. It’s vital to balance activities and downtime for the students. Making sure they have some time to relax and time to themselves each day is really important. I feel we managed this well on this trip.

3. It’s preferable to take two teachers. We were able to have a former teacher join the group in London and Paris, and it made a huge difference. Having two teachers spreads the worry, allows each teacher to have a little time off, and provides a backup in case of accidents. It’s also great to have one teacher wait with the group while the other buys tickets, etc.

Overall

This was a good trip overall. Students that went on both (the former Australia trip and this one) said this time was more fun and interesting. We did a lot, and I have almost 1000 photos to prove it.

However, it was far too stressful and could have gone wrong. For future trips we will need to do more preparation and research.

We’re thinking of going to Canada or Singapore next year. Anyone know any good schools? 😉