curriculum high school junior high school op-ed technology

by sendaiben

16 comments

IT education in Japan

I was talking to teachers at a school this week and went on a bit of a rant about how Japanese junior and senior high school students don’t do enough to acquire useful computer skills in school.

During a conversation afterwards, there seems to be an impression among teachers that IT skills involve using tablets, e-textbooks, and other new-fangled resources that they don’t understand.

That was not in the slightest what I was referring to.

I believe all students should acquire the following skills and competencies at school:

- Familiarity with computers, keyboards, mice

- Ability to do basic operations (turn on and off, launch programs, find things on the computer)

- Basic touch typing

- Use of word processors, spreadsheets, presentation software

- Ability to do basic research on the internet

- Ability to share data and collaborate online (via email or the cloud)

- Basic use of email (including spam awareness)

- Basic web design (elementary HTML) and blog creation

- Awareness of online safety issues (including identity theft)

Students should not only do this in their IT classes, but also practice and reinforce these skills in their other subject classes so that they come to see them as tools rather than content for a specific class.

This may seem basic and obvious to some readers, but as far as I can tell is not happening consistently across the board in Japan.

What do you think? Is anything missing from the list?

ALTs expectations high school junior high school SHS teaching

by sendaiben

leave a comment

Updating the ALT Playbook

A list of dos and don’ts for ALTs and other language teachers

I read Baye McNeill’s excellent book Loco in Yokohama a few weeks ago, and thoroughly enjoyed it. It’s a great read and it took me right back to my days teaching in junior high school as a first- and second-year ALT on the JET Programme.

It also reminded me of what I used to do in the classroom back then.

Like many ALTs, I came to Japan with little teaching experience (I had taught a couple of classes and done some tutoring in China). I received minimal training and very little supervision from my colleagues and supervisors, both in the school and in the local board of education. I got a lot of advice from other ALTs and just muddled through.

Thinking back now I can think of many ways I could have been more effective and served my students better. Don’t get me wrong, I think I did my best with the information I had and made a positive contribution, but I could have done so much more.

Here is my advice to ALTs and language teachers in Japanese junior and senior high schools:

- DO think about your goals for the year, the month, and the class. Lesson planning should end with the language target and textbook page, not start there. Try to link lessons together so that students can review and preview past and future activities and language.

- DON’T worry about things being fun. Video games are fun. Hanging out with your friends is fun. Language classes are seldom fun. Instead of fun, think about challenging, achievable, and meaningful. Success is the most motivating experience for students, and many of them are turned off by classes in which they never experience success. Give them that, and they will enjoy the class much more than if they had done some ‘fun’ activities. I haven’t seen many math classes here in Japan revolving around games, so why should language classes?

- DO think about time on task. Many classroom activities involve just one or two students, while all the others just watch or get bored. Games like pass the parcel, criss cross, and relay games were staples in my classroom, but I now believe that having students ask and answer simple questions in pairs for a couple of minutes would have been a much more useful activity. I bet many of the students would have enjoyed it more too.

- DON’T talk too much. I believe students need to use the language to acquire it, which in any class bigger than five students or so means doing pair or small group activities. Make sure there is a healthy balance of teacher talking time and student talking time in your class.

- DO set homework and encourage students to practice outside of class. Self-study using printed, audio, or online materials is the only realistic way for students to get good at English. Model appropriate activities in class and follow up to see what students are doing. Take an interest in the students who are practicing and keep nagging the ones that don’t.

- DON’T give up. I haven’t met a single student who doesn’t secretly want to be good at English. Keep giving them the chance to have a bit of success, to find something interesting to do in or with English, and you might be able to change their future relationship with the language.

What do you think of the list? Anything to add or disagree with?

high school jobhunting Language learning op-ed study abroad university

by sendaiben

7 comments

Japanese Students Studying Abroad

Here is an interesting article about Japanese students and the demand for study abroad programs (thanks Glenski).

*image stolen from the MOFA website

This seems to be a perennial topic of discussion, and there is much hand-wringing about how few students actually plan to study overseas.

To me this seems quite simple: I believe students are on the whole rational actors. Facing them are a range of issues:

- there are significant financial costs associated with studying overseas

- there is limited support for students to study overseas from universities and schools (generally students have to take time off from their studies)

- companies pay lip service to internationalization, but study abroad does not seem to help with job hunting and in fact hinders it greatly if students are away in their third and fourth years

- students don’t have the necessary language skills to study abroad after going through the normal English educational system in Japan

If these factors were flipped, particularly the third one, I am sure we would see interest rise.

What do you think? Is the system at fault or are Japanese students really the passive, docile, unadventurous generation that some media tries to make them out to be?

eikaiwa expectations high school JHS junior high school kids Language learning teaching vocabulary

by sendaiben

14 comments

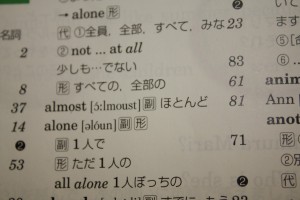

My ‘almost’ mini-lesson

Unfortunately, many students in Japan are taught that ‘almost’ in English is ‘hotondo’ in Japanese

Sadly this is not true, so over the years I have developed a short mini-lesson to correct this false impression and help students better understand the meaning of almost.

The lesson can start at any time, but it requires a trigger: one of the students must translate almost as hotondo.

Once that happens, I quickly go through the following steps:

- I point out that even though many teachers and textbooks teach this, almost is not the same as hotondo

- I pretend to trip, and then say “phew, I almost fell over just now”

- I ask the students to translate the previous sentence: “hotondo korobimashita” sounds really strange, so clearly hotondo is not a good translation here

- I tell the students I planned to go to Tokyo this morning, but ended up not going. “I almost went to Tokyo”

- “Hotondo Tokyo ni ikimashita” also sounds weird

- I offer two alternative translations for almost: mou chotto de ~ and ~wo suru tokoro datta

- I explain that hotondo is actually almost all in English: mou chotto de zenbu

Of course, this illustrates vividly the perils of learning and teaching vocabulary out of context, which provides another excellent mini-lesson for the students 🙂

Do you have any favourite mini-lessons?

conference curriculum extensive reading high school presentations university

by sendaiben

leave a comment

Step-by-step Extensive Reading Program Development

This is my workshop from the JALT national conference 2013: Step-by-step ER Program Development.

If you are interested in the topic, you can still get a free copy of our bilingual handbook for teachers here.