curriculum extensive listening extensive reading public policy

by sendaiben

4 comments

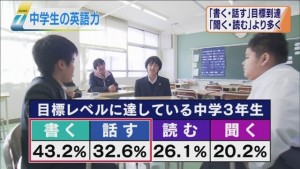

English Skills of Japanese Students

Business as Usual

Japan Times article. NHK puts a positive spin on the data. Less positive commentary.

Apart from unsurprised disappointment, my first reaction is to question what exactly the government thinks the equivalent of Eiken 3, pre-2, or 2 writing skills are that 40-odd percent of students have (given that these tests don’t have a writing section).

Is it that ridiculous ‘rearrange these words in the right order’ section? Because if they were using the words ‘writing skills’ in the form that the rest of the world understands, I think it would be a struggle for any Japanese junior and senior high school students to demonstrate proficiency.

I wrote about English education in Japan a couple of years ago in my ‘if I ruled the world’ series:

I don’t think a huge amount has changed since I wrote those. One thing that has changed for me is seeing how effective an extensive reading and listening course is. I will be doubling my efforts to get local schools to start their own programs -wish me luck.

Another MEXT announcement about English

Another week, another MEXT announcement about English education.

As usual, I agree with MEXT. Junior high school English classes would probably be more effective if they were done entirely in English. I remember learning French that way in the UK and it was mostly fine for me and my classmates. The main difference with Japan is that our teachers were fully trained, had opportunities to visit France to keep up their language skills, were able to use suitable materials, and enjoyed the support of colleagues, administrators, and parents. The exams in the UK also focused on communicative tasks.

I wish MEXT the best of luck with the implementation of this ambitious project, but I suspect we won’t be seeing these policies implemented in local schools any time soon. Personally, I am still trying to get our local high schools to start extensive reading programs… maybe 2014 will be the year?

Another Excellent Talk on Creativity

At the Oxford Day this year, I really enjoyed talking with Goodith White.

During her keynote, she mentioned this speech by Paul Collard, which I then tracked down and found excellent. He has some interesting points on teaching, test scores, and educational systems in Japan and Korea:

Lots of takeaways for language teachers. Some of the standouts for me:

- teachers need to train students to learn outside of the classroom

- our students are going to have to make their own jobs

- students that are pushed to achieve high educational test scores often end up disliking the subject and not pursuing it in the future (English in Japan?)

- autonomously functioning (self-directed) students do much better at university or in the workforce

What did you think of the speech?

More thoughts on (elementary school) English

I’ve had a few interesting conversations about this in the last couple of days, so I thought it might be good to summarize some of the ideas here.

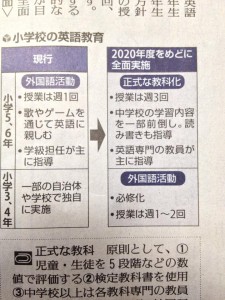

Here is a Yomiuri article (in Japanese) that summarises the proposals. Basically the government is leaning towards establishing English as a subject in elementary school years five and six. Being a subject would mean that students would receive grades, use textbooks, have three classes a week, and be taught by specialized teachers.

English (or international fun happy studies, or whatever they end up calling it) would also be introduced into years three and four as an activity: one class a week, no grades or textbooks, sounds like taught by homeroom teachers. Basically what the older kids are doing now.

The Good

- English in ES will have more legitimacy as a subject.

- Students will have more contact hours.

- The government has recognised that specialized teachers will be necessary.

- Younger students will have the chance to start with English.

The Bad

Basically nothing is bad as such in the announcement, but there are several important uncertainties:

- We don’t know how the government intends to recruit/train the ‘specialised teachers’.

- We don’t know how the curriculum will be developed.

- We don’t know what kind of materials will be available to teachers.

My Prediction

If we look at how things have turned out in the past with previous educational reforms, we don’t have much to be confident about.

I attended Cory Koby’s interesting presentation yesterday at the JALT National Conference, on the topic of the new Course of Study for Senior High School. He explained that although MEXT can issue recommendations, ultimately it is up to boards of education, schools, and individual teachers to carry them out.

I suspect that schools will not end up with experienced, English-speaking teachers for these classes. I suspect that the materials will be much the same as the ones we see now, and I suspect that the usual companies will seek to profit by offering inappropriate technological solutions.

The disconnect between policy makers and implementation can be particularly wide in Japan, and much as with previous policies (including the current ‘teach in English’ edict) I fear this will not trickle down to the chalkface.

Elementary School English (MEXT announcement)

Some big news from MEXT this week (courtesy of Kensaku Yoshida on Facebook)

Basically, from 2020 (estimated), 5-6 grade students will have English as a subject three times a week with specialist teachers. 3-4 grade students will have English activities once or twice a week.

The devil is in the details (see my recommendations here) but this looks like a step in the right direction!