Admin EFL extensive reading kids language courses readers Reading Review teaching

by sendaiben

6 comments

Children’s Readers Roundup

Rather than try to come up with a new topic every couple of days, I have decided to review all the children’s readers we use and write one post for each series. That should keep me going for a while, and hopefully turn into a useful resource for teachers considering their next purchase.

I have written briefly about a couple of series on the blog:

Story Street (10.12.22)

Oxford Reading Tree (10.10.23)

SRA (09.08.13)

but they were all fairly superficial posts. I plan to go much more in-depth this time around. There will also be a big comparison post at the end.

I’m quite excited about this project.

There is just one concern, which is the legality of posting content as part of a review. Does anyone know what is acceptable with regards to posting photos (of text, artwork, the outside cover of the book, CDs, etc.) taken by me?

I will probably contact the publishers just to make sure, but any advice or experiences would be much appreciated!

iPhone 4S in Japan

I almost let all the excitement go by without writing about this. Never fear, this blog does not hesitate to go off on tangents if I find them interesting.

The iPhone 4S was announced a couple of weeks ago, and came out last Friday in Japan. Personally I was disappointed. I’m a big iPhone fan and was expecting more. In this case, I think Apple’s marketing/hype machine actually worked against them.

I decided not to upgrade my 3GS, particularly after installing the new operating system (iOS 5) and having it work fine.

My wife, on the other hand, has a really old AU phone that is about to be discontinued (ie it won’t work on their network any more). She needs to upgrade, and this seemed like a good chance. I was also very curious to see how iPhone works on AU, as opposed to Softbank, my carrier.

My impressions of the iPhone 4S on AU (KDDI) in Japan:

1. AU has not carried the iPhone before, and as of last week their shop staff were undertrained and underprepared. Specifically, AU’s system for migrating address books from their cellphones to the iPhone leaves a lot to be desired, and the staff we were interacting with did not know how to use the software. We’ll probably end up typing all the numbers into gmail then syncing.

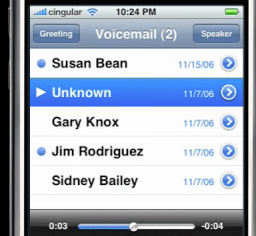

2. Voice mail on the AU iPhone is not visual!!! This is a huge negative, in my opinion. One of the iPhone’s greatest features was visual voicemail, where you could interact with each message individually and see details about them on your screen. AU seems to have kept the ‘call the voice mail centre and deal with it via keypad commands’. A horrible idea.

3. The battery life seems short. We burned through 50% in a couple of hours of trying it out (making calls, downloading apps, etc.).

4. It’s basically an iPhone 4 with better parts.

5. No tethering.

6. iPhone on AU is much more expensive than Softbank. Seems like at least an extra thousand yen a month, maybe more.

7. The camera is very nice.

I haven’t really spent enough time with it to comment on the network (Softbank certainly has issues, we’ll see how AU holds up as the wave of new iPhones get registered on their network).

My conclusion:

Having an iPhone is better than not having one, but for me at least, there is no need to upgrade to the 4S. The new iOS is worth getting though.

If you are considering switching to AU from Softbank, make sure you understand their pricing structure, etc. or you may get an unpleasant surprise.

What do you think? Have I made the right decision, or should I take advantage of Softbank’s free upgrade promotion? Comments very much appreciated.

curriculum EFL eikaiwa ES expectations extensive listening kids language courses Language learning listening school management self-study teaching

by sendaiben

6 comments

Practicing speaking with (young) learners

I am a strong believer in input-based learning, as that is how I best learn languages myself. However, recently I have started to question this approach, particularly but not exclusively for my younger students.

There does seem to be a ‘silent period’ for most learners, where they are more comfortable listening than speaking. This varies according to age and character, but seems to exist for all learners (even if it is just a few minutes for the most active/outgoing). I wouldn’t take it as far as this school (which enforces a silent period of about 6-8 months), but I like to keep it in the back of my mind.

The arguments for following a silent, input-heavy period seem pretty persuasive to me:

1. learners can get comfortable with the sounds of the language

This is important because if you can’t hear a sound, you’re unlikely to be able to produce it. There seems to be a case for delaying production until students have enough exposure to the sounds and rhythms of a language.

2. learners can become familiar with basic vocabulary and grammatical chunks

Assuming the input is at an appropriate level, learners will be able to hear the same vocabulary and grammatical chunks multiple times, beginning to acquire them.

3. learners can relax, lowering their affective filter and allowing them to focus on the language

This is pure TPR talk, but I find TPR extremely effective for beginners. Being able to sit back and not have to worry about performance seems to make it much easier for learners to pick up language.

However, this is a slow process. We’re talking about hundreds of hours.

In Japan, where most children learn English for an hour or less a week (elementary school age children at our school have 50-minute lessons), it is clearly not enough to expose children to appropriate input and wait for them to want to speak.

I think David Paul was very right to emphasise teaching children basic phonics so that they would be able to do reading and writing homework as soon as possible. I find children find it much easier to remember language when they have heard, said, read, and written it. It also has the happy side effect of seguing into extensive reading. Recently at Cambridge English we have been trying out various reader programs (Follifoot Farm, Story Street, Oxford Reading Tree, Springboard Readers, Rigby Star). On the whole students enjoy reading in class and for homework.

The other thing we have started doing recently is memorizing questions and answers and short dialogues. At first I wanted to make our own materials (something that may yet happen), but soon after that we came across MPI’s QA series, which does almost everything we want and saves us from reinventing the wheel. The books are not perfect, they have a few awkward questions in there and I’m not sure that the QA300 series really works, but they are cheap, easy to use, come with Japanese translations for students and parents to fall back on, and have CDs available.

So far I’ve been pleased with the results. Each student is set a few (2-10) questions to prepare each week, then has a test in their next class. If they can answer perfectly, they clear the question and get assigned new ones. If not, they review the same questions for the next class. Most students enjoy the challenge and are remembering more common questions. A few students love it and are shooting through the series, and some students are really struggling. As the students work individually at their own pace, this is not too much of a problem. On the whole , it’s been a positive development for our school.

So there we go. I still believe in input, but feel that it is not enough for a Japanese eikaiwa context. We supplement with reading and writing as well as memorising question and answer patterns, which seems to help but we’re still not completely where I would like us to be.

What do you think the most effective ways to teach children in an eikaiwa context are?

business conference curriculum EFL eikaiwa ES expectations extensive listening extensive reading kids language courses Language learning listening online resources presentations Reading school management self-study teaching technology theory university vocabulary

by sendaiben

8 comments

Amazing Minds 2011

I’m on the train on the way back to Sendai now, after a long, tiring, and wonderful weekend talking and learning about teaching. Pearson Kirihara was kind enough to invite me to their annual study meet, Amazing Minds, held in Tokyo this year.

The basic idea behind the event is that the publisher’s sales representatives nominate teachers all over Japan who are then contacted to see if they want to attend. Pearson picks up the tab for travel, accommodation, and food, and puts on a two-day program of presentations, discussions, and informal gatherings. Apparently it’s supposed to be a chance for the company to give back to the teaching community, to join and contribute to the dialogue on teaching in Japan, and to get to know individual teachers better.

I was initially skeptical, although having two of my friends (John Wiltshier and Ann Mayeda) presenting made it a lot easier for me to say yes and make the effort to clear my schedule.

The program for the event was three blocks: one on Saturday followed by dinner, then two on Sunday. Each block consisted of an initial one-hour lecture followed by a ninety-minute group activity session, and finally a feedback session to finish off. Each block was three and a half hours, a long time when you are out of practice concentrating. I got a good sense of what my university students go through most days (they have up to five ninety minute lectures per day).

The three lectures were:

“Two Pathways for Successful Language Learning”, John Wiltshier

“Teaching in 2020: Rethinking the Classroom Environment”, Ann Mayeda

“Lesson Analysis Checklist for Elementary School English Education”, Emiko Yukawa

I have to say I really enjoyed the presentations and came away with dozens of actionable ideas. Overall it was a great experience. I did notice a few things that could be tweaked to make it even better, but I have already passed those on to the organizers and don’t need to mention them here. Instead, I’d like to talk about the highlights.

Probably the biggest realization came during the first lecture, as John was talking about procedural and declarative memory, as well as the optimal period for language acquisition. It came to me quite suddenly that perhaps I am not a normal language learner. After all, I learned my first second language when I was five, in a total immersion environment. I have been at least intermediate in six languages, and find it fairly easy to pick up new ones mainly through input and trial and error. Very few people have this kind of background.

The problem is that I have made all sorts of assumptions about teaching and learning that are based on the possibly mistaken belief that my own experiences are generalizable -that I can teach my students as I would like to be taught and this will provide them with an optimal learning environment. If I am an outlier, however, this is unlikely to be ideal for my students. There will possibly be more effective ways of helping them learn and I will have to go back and examine literally everything I do once again with an open mind.

This seems fairly obvious when I write it here, but it seriously had not really occurred to me before.

Fortuitously, my beliefs about language learning are mainly a bias towards large amounts of input of the appropriate level, a desire to encourage my students to become self-directed and independent learners, and a tendency to believe that learners need to practice in order to improve (ie listen if they want to get better at listening, talk if they want to talk, and so on). I don’t think any of these are harmful.

The second, perhaps less revolutionary, but more specific breakthrough came from Ann’s presentation on flipping the classroom. Much like the Khan Academy, she is interested in ways teachers and learners can lever technology in order to do more outside the classroom, in turn allowing them to use their limited class time on more efficient or productive activities.

It’s a concept I have been very interested for a long time, as it ties in with my own beliefs about the best ways to learn a language.

Independent, self-directed learning is the only way students can possibly get the necessary amount of input and practice they will need to master English. The amount of time is several orders of magnitude larger than even the most specialized or intensive language course could provide. Using the power of the internet to facilitate this means that it is easier than ever for students to come into contact with foreign languages.

The only specifically new things for me in the presentation were several iPad/iPhone apps, but the real value came from the way I was reminded of various extremely promising ideas that I had meant to implement, but that had somehow ended up on the back burner.

Creating a Youtube channel for my students, pre-teaching things online so that students to go over them as many times as they need to in order to master them, introducing online resources in a more systematic way, monitoring and advising students as they explore various self-study options.

Hopefully I’ll be able to get started on one or more of these in the near future. I will definitely keep you posted.

Finally, Yukawa-sensei’s presentation gave me a good look at a systematic way of assessing classes and lesson plans. Again, there was nothing new in this presentation, but it was a great opportunity to once again go back and think about things in a slightly different light.

I used to do a lot of classroom observation when I was the ALT Advisor at the Miyagi Board of Education, and although I didn’t have anything as elegant as Yukawa-sensei’s checklist, I was looking at similar things.

I’ll be applying to checklist to my own classes this week, and predict that I will find several areas to work on during the next few months.

I really enjoyed the weekend and hope Pearson continues putting on these events for teachers and that they consider having me back again sometime.

curriculum EFL expectations extensive reading language courses Language learning readers Reading self-study teaching theory university

by sendaiben

5 comments

Extensive Reading, Goals, and Benevolent Tyranny

I received an email from Tom Robb this morning, creator of the Moodle Reader (a fantastic free resource to track and verify student reading within an ER program), very kindly answering some questions I asked him.

Among them he mentioned that I seem to be setting quite ambitious goals for my students in terms of the amount of reading I expect them to do. This isn’t the first time I’ve heard that comment, so I thought this would be a good chance to expand on the topic, as well as discuss a couple of peripheral issues that are pertinent to it.

First of all, in my extensive reading classes at Tohoku University, I require students to read at least 100,000 words in one semester. That is the amount of reading they have to do to pass the course and receive a credit. Beyond that, if they want to get an A or AA grade (the top grade), they have to read much more. Generally to have a chance of getting an AA, students would have to read around half a million words.

Talking to other teachers, I seem to have set the bar rather high.

The thing is, extensive reading (and language learning in general) is a numbers game. It’s not so much about what you do (although doing things that work for you does speed the process up) as it is about how much you do. How much reading do you do. How many words, books, hours? The more you do, the easier it becomes and the more you learn. There is a critical mass involved, too. According to Nishizawa et al. the turning point for their students came after they had read 300,000 words: after that, they found it much easier to read in English.

The flipside of this is that if you don’t read enough, you probably won’t reach this breakthrough moment.

I push my students hard. They are academically gifted, often motivated, and understand the reasons why they have to work so hard. The most committed report spending more than ten hours a week reading for my class.

None of my students failed to reach the 100,000 word level, and most of them did much better. I’m very proud of them.

There are several reasons I push them so hard. One is that they have a lot of catching up to do: very few of them have done much in the way of extensive reading or listening in their English learning so far. They have a great deal of knowledge about English (in the form of grammar patterns and knowing a Japanese translation for a lot of English words), but not as much familiarity with it (reading or listening fluency, knowledge of collocations, sense of register). They need a lot of input to catch up to their peers in other countries.

I’m also hoping to get them started on a habit of English. Creating a habit is often just a matter of gradually integrating it into your daily routine, so that it becomes ingrained, like brushing your teeth or reading a newspaper in the morning. If my students are going to have a shot at becoming proficient English users, they are going to have to make it a part of their lives. A semester is not a very long time, but I hope that at least some of my students will catch the reading bug and continue reading in English for an hour or two each week after the course is over.

Finally, I set ambitious goals for my students because they are very bright and very busy.

Busy people naturally try to optimise their time, spending it on more urgent or important things, while sometimes neglecting the less urgent but more important goals (getting mired in quadrant three from the Seven Habits of Highly Effective People) . I am the same -I know that I should be spending an hour or so a day learning Thai, but instead find myself catching up on grading because it is due tomorrow morning. By having high expectations of my students and setting them concrete goals I hope to push them a little closer towards the goal of English proficiency.

Not all of them will continue reading, of course. But some will. And even the ones that don’t will find themselves reading a little bit more quickly and easily.

Do you agree with setting ambitious targets? Can it sometimes be harmful? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below.