VUS TESOL 2014

I am extremely excited to have the chance to speak at VUS TESOL 2014 in Ho Chi Minh City this year. Slides, notes, and hopefully video to follow next week.

The website for the event is here.

Welcome to the desert of the real

The march of technology continues

Microsoft announced a new product the other day: simultaneous interpretation over Skype.

Also Google bought Word Lens last week and made all their products free. Check it out and blow your mind.

How can this not impact language teaching and learning?

Oh, and the Google robot cars are one step closer:

Micro or Macro Teaching?

Are you seeing the big picture?

Just as in economics, there seem to be two main approaches to education.

Micro teaching involves discrete items and lesson plans. Macro teaching, on the other hand, deals with skills, motivation, and long-term goals.

Clearly both are necessary, but it is easy for teachers to focus exclusively on micro education: after all, that is what they have control over and what students and administrators are likely to look at.

For the last couple of years, first with extensive reading and then with discussion courtesy of my collaborator Daniel E, I have been focusing on macro approaches. For certain contexts, particularly ones where students have already spent a lot of time focusing on discrete language, a focus on general language skills, independent study, input , and content works really well.

This year I will be making an effort to try something similar with students at Cambridge English.

The rumoured teacher handbook for teaching discussion classes is also becoming more real day by day. I’ll keep you posted.

ALTs expectations high school junior high school SHS teaching

by sendaiben

leave a comment

Updating the ALT Playbook

A list of dos and don’ts for ALTs and other language teachers

I read Baye McNeill’s excellent book Loco in Yokohama a few weeks ago, and thoroughly enjoyed it. It’s a great read and it took me right back to my days teaching in junior high school as a first- and second-year ALT on the JET Programme.

It also reminded me of what I used to do in the classroom back then.

Like many ALTs, I came to Japan with little teaching experience (I had taught a couple of classes and done some tutoring in China). I received minimal training and very little supervision from my colleagues and supervisors, both in the school and in the local board of education. I got a lot of advice from other ALTs and just muddled through.

Thinking back now I can think of many ways I could have been more effective and served my students better. Don’t get me wrong, I think I did my best with the information I had and made a positive contribution, but I could have done so much more.

Here is my advice to ALTs and language teachers in Japanese junior and senior high schools:

- DO think about your goals for the year, the month, and the class. Lesson planning should end with the language target and textbook page, not start there. Try to link lessons together so that students can review and preview past and future activities and language.

- DON’T worry about things being fun. Video games are fun. Hanging out with your friends is fun. Language classes are seldom fun. Instead of fun, think about challenging, achievable, and meaningful. Success is the most motivating experience for students, and many of them are turned off by classes in which they never experience success. Give them that, and they will enjoy the class much more than if they had done some ‘fun’ activities. I haven’t seen many math classes here in Japan revolving around games, so why should language classes?

- DO think about time on task. Many classroom activities involve just one or two students, while all the others just watch or get bored. Games like pass the parcel, criss cross, and relay games were staples in my classroom, but I now believe that having students ask and answer simple questions in pairs for a couple of minutes would have been a much more useful activity. I bet many of the students would have enjoyed it more too.

- DON’T talk too much. I believe students need to use the language to acquire it, which in any class bigger than five students or so means doing pair or small group activities. Make sure there is a healthy balance of teacher talking time and student talking time in your class.

- DO set homework and encourage students to practice outside of class. Self-study using printed, audio, or online materials is the only realistic way for students to get good at English. Model appropriate activities in class and follow up to see what students are doing. Take an interest in the students who are practicing and keep nagging the ones that don’t.

- DON’T give up. I haven’t met a single student who doesn’t secretly want to be good at English. Keep giving them the chance to have a bit of success, to find something interesting to do in or with English, and you might be able to change their future relationship with the language.

What do you think of the list? Anything to add or disagree with?

eikaiwa expectations high school JHS junior high school kids Language learning teaching vocabulary

by sendaiben

14 comments

My ‘almost’ mini-lesson

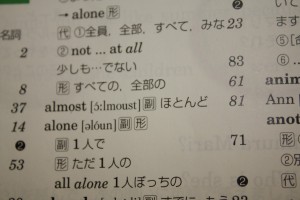

Unfortunately, many students in Japan are taught that ‘almost’ in English is ‘hotondo’ in Japanese

Sadly this is not true, so over the years I have developed a short mini-lesson to correct this false impression and help students better understand the meaning of almost.

The lesson can start at any time, but it requires a trigger: one of the students must translate almost as hotondo.

Once that happens, I quickly go through the following steps:

- I point out that even though many teachers and textbooks teach this, almost is not the same as hotondo

- I pretend to trip, and then say “phew, I almost fell over just now”

- I ask the students to translate the previous sentence: “hotondo korobimashita” sounds really strange, so clearly hotondo is not a good translation here

- I tell the students I planned to go to Tokyo this morning, but ended up not going. “I almost went to Tokyo”

- “Hotondo Tokyo ni ikimashita” also sounds weird

- I offer two alternative translations for almost: mou chotto de ~ and ~wo suru tokoro datta

- I explain that hotondo is actually almost all in English: mou chotto de zenbu

Of course, this illustrates vividly the perils of learning and teaching vocabulary out of context, which provides another excellent mini-lesson for the students 🙂

Do you have any favourite mini-lessons?