iPhone 4S in Japan

I almost let all the excitement go by without writing about this. Never fear, this blog does not hesitate to go off on tangents if I find them interesting.

The iPhone 4S was announced a couple of weeks ago, and came out last Friday in Japan. Personally I was disappointed. I’m a big iPhone fan and was expecting more. In this case, I think Apple’s marketing/hype machine actually worked against them.

I decided not to upgrade my 3GS, particularly after installing the new operating system (iOS 5) and having it work fine.

My wife, on the other hand, has a really old AU phone that is about to be discontinued (ie it won’t work on their network any more). She needs to upgrade, and this seemed like a good chance. I was also very curious to see how iPhone works on AU, as opposed to Softbank, my carrier.

My impressions of the iPhone 4S on AU (KDDI) in Japan:

1. AU has not carried the iPhone before, and as of last week their shop staff were undertrained and underprepared. Specifically, AU’s system for migrating address books from their cellphones to the iPhone leaves a lot to be desired, and the staff we were interacting with did not know how to use the software. We’ll probably end up typing all the numbers into gmail then syncing.

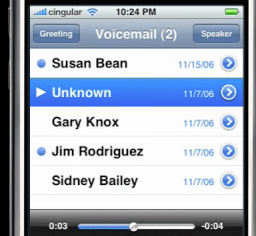

2. Voice mail on the AU iPhone is not visual!!! This is a huge negative, in my opinion. One of the iPhone’s greatest features was visual voicemail, where you could interact with each message individually and see details about them on your screen. AU seems to have kept the ‘call the voice mail centre and deal with it via keypad commands’. A horrible idea.

3. The battery life seems short. We burned through 50% in a couple of hours of trying it out (making calls, downloading apps, etc.).

4. It’s basically an iPhone 4 with better parts.

5. No tethering.

6. iPhone on AU is much more expensive than Softbank. Seems like at least an extra thousand yen a month, maybe more.

7. The camera is very nice.

I haven’t really spent enough time with it to comment on the network (Softbank certainly has issues, we’ll see how AU holds up as the wave of new iPhones get registered on their network).

My conclusion:

Having an iPhone is better than not having one, but for me at least, there is no need to upgrade to the 4S. The new iOS is worth getting though.

If you are considering switching to AU from Softbank, make sure you understand their pricing structure, etc. or you may get an unpleasant surprise.

What do you think? Have I made the right decision, or should I take advantage of Softbank’s free upgrade promotion? Comments very much appreciated.

ALTs business EFL eikaiwa ES expectations JHS kids life in Japan school management teaching teaching culture Uncategorized university

by sendaiben

5 comments

Skewed rewards and incentives (why are university teachers at the top of the pile?)

I have taught at private language schools, public elementary, junior high, and senior high schools, and universities in Japan. They roughly rank in that order in terms of prestige, financial remuneration, and ease of getting a job.

A job at an eikaiwa school is the easiest to get, the worst paid, and has the least amount of prestige (want proof? See how estate agents treat you). Working in public schools is better paid, more challenging to get, and is perceived as being higher by society (some of the dwindling prestige of public school teachers rubs off). Finally, a university position tends to pay rather well, involves jumping through various hoops (publications, experience teaching at the tertiary level, Japanese ability, postgraduate qualifications), and confers a reasonably high status (varying somewhat according to the institution in question).

Seemingly illogically, the actual amount of skill required to do the job well seems to run in the opposite direction. I would say, based on my experience, teaching at an eikaiwa, where you will probably have students ranging from 3 to 70 years old, and classes that run the gamut from 40 kindergarteners to one sleep-deprived businessman or a group of senior citizens, requires the most skill to perform well.

Teaching in public schools can provide discipline challenges, but the range of teaching situations is less varied and the curriculum provides a framework that reduces the amount of material teachers need to master.

Finally, teachers at the university level probably need the least amount of teaching skill to get by: their students are selected for academic potential (yes, even at the worst universities) and teachers tend to have the freedom to decide on the content of their classes. University teachers are pretty much encouraged to teach to their strengths, and can get away with teaching a narrow range of material if they so choose.

So why are the positions that need the most skilled teachers the worst paid?

You can see something similar even within public schools: kindergarten teachers are the least well paid and regarded, followed by elementary school teachers, then junior high school teachers, and finally high school teachers. However, if we look at the potential impact that teachers can have upon their charges, the early years are far more influential. Children who have excellent teachers during the first years of their schooling, then mediocre ones later, are likely to do much better than children in the opposite situation. Why then does society seem to have its priorities so badly skewed?

Is this fixable? Can you imagine a world where kindergarten teachers are given the pay, training, and status the importance of their job deserves? Will the cushiness of university positions be reflected in salaries?

As always, comments very much appreciated below.

earthquake life in Japan living in Japan personal refugee

by sendaiben

5 comments

The Great East Japan Disaster Part Three: Refugee 1.0

The third installment. See Part One and Part Two if you are confused.

The Great East Japan Disaster Part Three: Refugee 1.0

The actual drive from Sendai to Kanazawa was nightmarish, not because it was particularly bad, but rather because it seemed vividly unreal.

We left the house about 2:30am, and headed south on Route 4 as the expressways were all closed due to the earthquake. We had half a tank of fuel, something that will become significant shortly. The power was off everywhere, so we had to slow down at each intersection to check for cars. No lights in houses, no street lights, no traffic lights. It was strangely peaceful and slightly eerie, with no other cars to be seen. The roads in the southern part of Sendai were not damaged, unlike the east of the city where our classroom is, where they buckled and cracked dramatically.

After an hour or so I couldn’t keep my eyes open, so I got my wife to take over driving duties and napped in the passenger seat. We were just north of Fukushima city at that point.

Of course, we had originally planned to go west then down the Sea of Japan coast. Unfortunately the fact that we only had half a tank of petrol made it seem more sensible to use the main roads to the south, even if that did take us closer to the reactor than we were comfortable with. Remember, at this point all we knew is that the plant was at risk, so we were very nervous about worst case scenarios (in hindsight, with some justification!).

After a couple of hours of sleep, I woke up and resumed driving. We passed through town after town, all silent and dark, and it wasn’t until we reached the southern end of Fukushima that the electricity came back on. Even then, shops and more importantly, petrol stations were closed and boarded up.

Further and further south we drove, with the fuel gauge dropping lower and lower. It was just outside Utsunomiya that I started getting seriously worried. The needle hit the bottom of the red section, and I figured we probably had about ten kilometres left before we had to ditch the car.

Suddenly we passed a petrol station with a small line of about five cars. It didn’t register for a few seconds, but then I pulled a very sharp u-turn and five minutes later we were in front of a pump. They were out of ordinary petrol, but still had four-star (premium, high-octane). I gratefully filled the tank, and we were on our way.

As we drove on, I realised how lucky we had been to drive past a petrol station that had just opened. Every other one we say for the next hour or two had a line of twenty to thirty cars waiting, or was closed.

The rest of the day was fairly ordinary. We had lunch at a Sukiya (a chain restaurant), stopped at a couple of convenience stores, drove through the most amazing scenery I have seen in Japan (Nagano and Toyama), and finally got to Kanazawa around 6pm, roughly fifteen hours after we set off.

That night we went to a sento (public bathhouse) and out to dinner. It was wonderful.

The Great East Japan Disaster Part Two: Nuclear Accident

Continuing my account of the March 2011 disaster. See Part One for the beginning of the tale.

Part Two: Nuclear Accident

Around 6pm on Saturday evening (the day after the earthquake), just after we had eaten and just as we were thinking about going to bed (with no power and no heat, you quickly revert to a more natural sleep cycle!), our phone rang. Now, given that we had no power and the phones were supposed to be out, this was fairly surprising.

We actually got phone calls from two people that evening: my uncle in the UK, and my godfather in Germany. Both were calling because of initial reports of the nuclear power plant accident in Fukushima.

There wasn’t much information at that point, just reports that the cooling systems were broken and the reactors might be breached. I talked to both of them briefly, then hung up and went to talk to my family. Before convincing them though, I had to convince myself. Remember, I had spent seven hours driving a 30km round trip the day before. I knew how the roads would end up if everyone in Sendai decided to evacuate. We wouldn’t get ten miles…

That’s what decided it for me. Go now, or risk never being able to go. We had to leave immediately.

The other factor was to run through the possible outcomes of the decision. I first remember seeing this in a video about climate change, of all things. You can check it out here.

I did the same thing with our possible escape. Run away/stay put. Nuclear accident is harmless/catastrophic. Made a funky box decision matrix thing, and compared the worst case scenarios: we ran away and the nuclear accident was harmless. We feel a bit silly, it costs us some money. We didn’t run away, and the nuclear accident was catastrophic. Hollywood disaster movie ensues, with us as extras (ie not the people that get picked up in the presidential helicopter just in time).

Once I got that clear in my head, I quickly persuaded my wife and kids. We decided to leave immediately, except that my wife didn’t want to leave her parents behind, so we sent one of the girls to get them. Another of them had gone to take some food to her colleagues just before we got the phone calls, so we had to wait for her too.

It was a tense wait, sitting around the kerosene stove. We put the candles out to save them and grabbed a change of clothes and some personal items. I couldn’t find my youngest daughter’s passport, and the eldest’s one had expired. Figured we could sort something out later.

Coincidentally, my wife’s cousin who lives in Kanazawa on the other side of Japan called her just after the earthquake and before the phones went down, offering her a place for us to stay. We decided to head that way as I had a vague notion to head for Osaka and ultimately abroad to Thailand or the UK if things went really bad, and Kanazawa is on the way to Osaka (and more than 600km from the nuclear reactor across a major mountain range). It seemed to be a good choice.

A good two hours later, my parents in law showed up. Apparently it wasn’t traffic, but rather the fact that it took that long to persuade them to come with us that had caused the delay. They didn’t really see the problem, didn’t want to go (especially in the middle of the night), and were not convinced there was a problem. After all, the government was saying it was okay…

After pacifying them, we sent them off first with two of the girls at about 22:30, telling them to drive across to the Sea of Japan, then down the coast to Kanazawa. The one huge problem was fuel, as shortages, damaged petrol stations, power cuts, and panic buying had rendered it almost impossible to find in Sendai. I figured we’d find some once we got out of the earthquake zone.

So we waited for our eldest to come back. And waited. And waited some more. At around 0:30 my wife went to bed while I stayed up. It was 2am when our daughter came back, so I quickly told her what was going on, gave her ten minutes to pack, and got my wife up.

Jumping into the car, we looked at the half-full petrol tank and thought about distances and routes.

Before we left, we set out as much water and food for our cats as we could, then said goodbye to them.

The Great East Japan Disaster Part One: Earthquake

Okay, so I am going to hijack my own blog to shamelessly share some thoughts and experiences from the last few weeks. This is partly in order to give myself an outlet, as well as to provide an easily accessible record I can refer friends and family to. Don’t worry, we’ll be going back to educational topics soon enough.

Part One: Earthquake

When the earthquake happened I was in one of the Cambridge English classrooms. I was supposed to be observing a kids’ class from 15:40, as one of our teachers was leaving, and we were just setting up and cleaning the classroom.

At 14:46 the earthquake started. For a week or so beforehand, we’d had a series of smaller earthquakes, so we weren’t particularly worried. I moved to the back door and opened it and the other teacher did the same at the front. However, the shaking continued much longer than usual, and got stronger and stronger. It got to the point where we had to force ourselves not to run outside (leaving the building during an earthquake is usually more dangerous as you are more likely to be injured by falling objects or broken glass than by a building collapse).

The earthquake had gone on for several minutes, when suddenly there was a sharp sideways motion, and everything in the room that wasn’t fixed down (and a few things that were, like shelves that were screwed into the wall) flew sideways. Computers, printer, plant pots, and hundreds of books were launched into the air and ended up in big piles on the floor.

Thankfully, it stopped shortly after that.

Walking outside, we went to check on friends who run a restaurant nearby. They were fine, but the restaurant was a real mess, with broken glasses and bottles everywhere. We decided to wait outside in a nearby park, away from power lines and buildings, just in case.

It was a very cold day, not the kind of weather you want to be standing outside in the cold for. We did that for an hour or so and experienced several aftershocks. Then it started snowing, so we set off for home by car. The roads were jammed, and damaged in places. Some sections were cracked, or bulged up, or had collapsed. I tried to call or email my family, but everything was down (after an earthquake, everyone tries to call at once and the system gets overloaded). Fortunately, Facebook was working so managed to get in touch with family and friends that way.

Social networks really came into their own during the disaster, allowing people to keep in touch and organise themselves.

Anyway, after two hours in stop-start traffic, we got home. The power was out throughout the city, so none of the traffic lights worked. Surprisingly, there were no accidents and everyone became really considerate drivers. Once it got dark the streets became dangerous, as the streetlights were also out. Pedestrians and cyclists were almost impossible to see. Lines of people formed at public phones, as they seemed to still be working.

At home we broke out some candles and tried to keep warm. Our house is quite old, so we have several kerosene heaters. Most of them require electricity, but luckily two of them are the old stove type so we managed to get them going.

It was pretty eerie: the blacked out silent city where the only noises were the sirens of emergency vehicles in the distance. It was the first time I saw the stars in Sendai.

That evening we went to our local refuge (each neighborhood in Japan has a designated place people should go to in a disaster -usually a school) but they didn’t have any food or water yet. We also went to check on another of our teachers, as well as family members. What should have been an hour’s drive took seven hours, and we got back home at 3am.

At one point we had to drive through water (in Nakano Sakae near Tagajo) but we had no idea of the significance. With no power we were not getting much news so we had no idea of the true scale of the tragedy on the coast. Despite the blackouts, we didn’t think too much of the earthquake as there was not much damage to buildings: they held up incredibly well.

The next day we again drove out to check on our classrooms and one of the girls’ apartment, taking food and drink and leaving everything else. We managed to find an open shop where we bought vegetables and were feeling quite positive by the time we got home. Cooking on the kerosene heaters was slow but worked, and we had a simple dinner of fish and vegetables, which was great after 24 hours of eating chocolate and snacks.

Full, warm, and safe, we faced our second night after the earthquake in good spirits (remember, we still had no real news about the scale of things).