curriculum EFL expectations extensive reading language courses Language learning readers Reading self-study teaching theory university

by sendaiben

5 comments

Extensive Reading, Goals, and Benevolent Tyranny

I received an email from Tom Robb this morning, creator of the Moodle Reader (a fantastic free resource to track and verify student reading within an ER program), very kindly answering some questions I asked him.

Among them he mentioned that I seem to be setting quite ambitious goals for my students in terms of the amount of reading I expect them to do. This isn’t the first time I’ve heard that comment, so I thought this would be a good chance to expand on the topic, as well as discuss a couple of peripheral issues that are pertinent to it.

First of all, in my extensive reading classes at Tohoku University, I require students to read at least 100,000 words in one semester. That is the amount of reading they have to do to pass the course and receive a credit. Beyond that, if they want to get an A or AA grade (the top grade), they have to read much more. Generally to have a chance of getting an AA, students would have to read around half a million words.

Talking to other teachers, I seem to have set the bar rather high.

The thing is, extensive reading (and language learning in general) is a numbers game. It’s not so much about what you do (although doing things that work for you does speed the process up) as it is about how much you do. How much reading do you do. How many words, books, hours? The more you do, the easier it becomes and the more you learn. There is a critical mass involved, too. According to Nishizawa et al. the turning point for their students came after they had read 300,000 words: after that, they found it much easier to read in English.

The flipside of this is that if you don’t read enough, you probably won’t reach this breakthrough moment.

I push my students hard. They are academically gifted, often motivated, and understand the reasons why they have to work so hard. The most committed report spending more than ten hours a week reading for my class.

None of my students failed to reach the 100,000 word level, and most of them did much better. I’m very proud of them.

There are several reasons I push them so hard. One is that they have a lot of catching up to do: very few of them have done much in the way of extensive reading or listening in their English learning so far. They have a great deal of knowledge about English (in the form of grammar patterns and knowing a Japanese translation for a lot of English words), but not as much familiarity with it (reading or listening fluency, knowledge of collocations, sense of register). They need a lot of input to catch up to their peers in other countries.

I’m also hoping to get them started on a habit of English. Creating a habit is often just a matter of gradually integrating it into your daily routine, so that it becomes ingrained, like brushing your teeth or reading a newspaper in the morning. If my students are going to have a shot at becoming proficient English users, they are going to have to make it a part of their lives. A semester is not a very long time, but I hope that at least some of my students will catch the reading bug and continue reading in English for an hour or two each week after the course is over.

Finally, I set ambitious goals for my students because they are very bright and very busy.

Busy people naturally try to optimise their time, spending it on more urgent or important things, while sometimes neglecting the less urgent but more important goals (getting mired in quadrant three from the Seven Habits of Highly Effective People) . I am the same -I know that I should be spending an hour or so a day learning Thai, but instead find myself catching up on grading because it is due tomorrow morning. By having high expectations of my students and setting them concrete goals I hope to push them a little closer towards the goal of English proficiency.

Not all of them will continue reading, of course. But some will. And even the ones that don’t will find themselves reading a little bit more quickly and easily.

Do you agree with setting ambitious targets? Can it sometimes be harmful? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

ALTs business EFL eikaiwa ES expectations JHS kids life in Japan school management teaching teaching culture Uncategorized university

by sendaiben

5 comments

Skewed rewards and incentives (why are university teachers at the top of the pile?)

I have taught at private language schools, public elementary, junior high, and senior high schools, and universities in Japan. They roughly rank in that order in terms of prestige, financial remuneration, and ease of getting a job.

A job at an eikaiwa school is the easiest to get, the worst paid, and has the least amount of prestige (want proof? See how estate agents treat you). Working in public schools is better paid, more challenging to get, and is perceived as being higher by society (some of the dwindling prestige of public school teachers rubs off). Finally, a university position tends to pay rather well, involves jumping through various hoops (publications, experience teaching at the tertiary level, Japanese ability, postgraduate qualifications), and confers a reasonably high status (varying somewhat according to the institution in question).

Seemingly illogically, the actual amount of skill required to do the job well seems to run in the opposite direction. I would say, based on my experience, teaching at an eikaiwa, where you will probably have students ranging from 3 to 70 years old, and classes that run the gamut from 40 kindergarteners to one sleep-deprived businessman or a group of senior citizens, requires the most skill to perform well.

Teaching in public schools can provide discipline challenges, but the range of teaching situations is less varied and the curriculum provides a framework that reduces the amount of material teachers need to master.

Finally, teachers at the university level probably need the least amount of teaching skill to get by: their students are selected for academic potential (yes, even at the worst universities) and teachers tend to have the freedom to decide on the content of their classes. University teachers are pretty much encouraged to teach to their strengths, and can get away with teaching a narrow range of material if they so choose.

So why are the positions that need the most skilled teachers the worst paid?

You can see something similar even within public schools: kindergarten teachers are the least well paid and regarded, followed by elementary school teachers, then junior high school teachers, and finally high school teachers. However, if we look at the potential impact that teachers can have upon their charges, the early years are far more influential. Children who have excellent teachers during the first years of their schooling, then mediocre ones later, are likely to do much better than children in the opposite situation. Why then does society seem to have its priorities so badly skewed?

Is this fixable? Can you imagine a world where kindergarten teachers are given the pay, training, and status the importance of their job deserves? Will the cushiness of university positions be reflected in salaries?

As always, comments very much appreciated below.

business EFL eikaiwa ES expectations kids language courses Language learning school management teaching teaching culture

by sendaiben

2 comments

The purpose of a language school

This year has given me a lot to think about with regards to Cambridge English, the language school I help run. We have been forced to make a lot of changes, closing one location, rearranging the schedule to deal with staff shortages, developing the curriculum to move towards where we want the school to be.

I have also had the chance to do a lot of teaching during the last six months, averaging around 60 contact hours a week and coming very close to burning out.

Brainstorming with other staff has given me some broad principles to follow in the future, and interestingly shows where we went wrong in the past. Some of our previous goals were in fact counter-productive and were holding us back. It has also thrown out some dilemmas that I have not completely resolved yet.

Big or small?

This is probably the first question school owners need to answer. Do you want to be a big school with multiple locations and a large staff, or a small school? We used to want to be big, but it is a horrendous amount of work to grow beyond a couple of teachers, and I am not sure that it is possible to do so without taking a considerable hit in terms of character and quality. Multiple locations means doubling up on resources, something that is almost prohibitively expensive for us (we have thousands of readers and a lot of games and toys). Moving things to where they need to be and keeping track of things is a huge headache that doesn’t exist when you are based in one place.

So, I give up. I am never going to be the CEO of a big company. My talents and temperament don’t seem to be a good fit with that. Instead, I will see how far we can take things on a more manageable scale.

Cheap or expensive?

This is another vital question, one that has become a bit of a no-brainer for us. I believe there is no future for small schools attempting to compete on price. I even feel that charging average fees is a losing proposition for us. Instead, we are going to attempt to become a boutique school, a luxury good in economic terms. As long as your market is large enough (we are in Sendai, a medium-sized city), there should be plenty of potential customers for whom quality is more important than price.

Of course, if you want to charge more, you also have to deliver results. Your classes must be purposeful and show students or their parents how they are helping them. Your school should be attractive, clean, and well-presented. You should have an effective curriculum and decent staff. Effective communication with students and/or parents is also essential.

Provided you actually deliver these things, charging more than other schools around you can be an effective marketing technique. For certain potential customers, higher prices are likely to catch their attention. Why is that school more expensive? In a lot of cases, higher prices will give an image of higher quality.

We have found that each time we raise our prices, demand also rises. Take private lessons for adults: we started at the ridiculously low price point of 8,000 a month for four classes, then raised it to 12,000, then doubled it to 24,000. Each time we raised the price, we got a wave of new enquiries.

Inclusive or exclusive?

This is something I have real trouble with. Our school has always tried to accommodate all students, regardless of their ability or temperament. We have several students with mental or emotional disabilities, and most of them have private classes at group rates because that is the most effective way to meet their needs and the needs of other students.

However, in line with the drive for quality above, I am tempted to screen students entering our school. Often when students come for trial lessons, it is very easy to tell if they are actually interested in English or not. It is also fairly easy to predict how involved their parents are likely to be, or how interested they are in the school.

Motivated students with supportive parents are easy to teach and learn quickly. This leads to a virtuous circle of achievement, where the students learn more, get more satisfaction, and are driven to learn even more.

If you eliminate the disinterested, the disruptive, the disturbed, and the less able, classes will go more smoothly and both students and teachers will enjoy them more. Students are more likely to succeed in this case, and success leads to very effective word of mouth marketing. If you also get a reputation for being selective, then that can increase interest in your school, as people always want things they can’t have.

However, is this fair? As a teacher, I feel a duty to society. If we only take students that can afford to pay elevated fees, we are depriving poorer, possibly equally motivated and able students, of the chance to study with us. If we turn away students with behavioural, emotional, or educational problems, we are discriminating against them as well. Don’t all students have the right to have access to what we can offer them?

Of course, we are a business, not a public school. We can set any policy we like, take or turn away any customer, and set fees at any level.

One way to square this circle is to provide options to accommodate different students. We currently have half a dozen students who are studying for free, because their family circumstances due to divorce, unemployment, or the after effects of the earthquake means that they would not have been able to remain with us as paying students. We also have students who receive private lessons for the price of group ones because they are autistic and do not work well with others: we didn’t feel it was fair to charge them more because of their disability. Perhaps we can extend this model into the future, providing academic scholarships for promising students who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford the fees and continuing to cater to non-standard students.

So, what is the purpose of a private language school?

Is it solely a profit-making enterprise or is there some obligation to serve the community? How do you address these three issues? I would be very interested to hear from other owners and teachers in the comments below.

Amazon.com EFL eikaiwa kids language courses Language learning vocabulary

by sendaiben

3 comments

Apples to Apples Junior (board game review for EFL teachers)

I received a copy of this game from a friend a few weeks back, and just got around to trying it with a class of junior high school students yesterday.

Basically the game consists of one player laying down an adjective card, like ‘scary’, and then the other players laying down nouns, like ‘car accident’, ‘octopus’, or ‘tree house’. The original player then chooses which of the nouns they feel is closest in meaning to the adjective or most appropriate. Players can also choose ridiculous or illogical cards if they want. The player that laid down the card that was chosen gets a point, and another player gets to decide the next adjective.

This game worked extremely well, as students had to understand all the words in order to play. There was a lot of asking and dictionary use, and students really seemed to enjoy the game. Being the junior version, the language used was appropriate for my keen junior high school students. I would estimate that they knew about half the words involved. We played for about fifteen minutes, but it would be just as easy to have shorter games once the students are used to the rules and start learning the language.

One thing I really like is that the adjective cards list two or three synonyms, and the noun cards have some simple facts or jokes printed on them, so there is a lot of potential for students to move beyond the basic vocabulary.

The game contains almost 600 word cards, so should be a useful resource for the long term. I thoroughly recommend this game, with the caveat being that it does not seem to be available in Japan, and amazon.com will only ship it to a US address. Still, if you can get hold of a copy, I think you’ll like it!

curriculum EFL eikaiwa expectations kids language courses Language learning readers Reading school management self-study teaching university

by sendaiben

7 comments

5 Top Extensive Reading Hacks for Teachers

I am a huge fan of extensive reading (ER), and believe it is an essential part of any language course. Also known as FVR (free voluntary reading, although the voluntary part is kind of optional, as you’ll see below), it basically consists of reading a large amount of easily understood text. This usually delivers fairly painless language acquisition, as well as the ancillary benefits of enjoyment and incidental content learning. You can learn more about ER at the Extensive Reading Foundation page.

I’ve been doing ER with Japanese learners since 2004, and have found a few techniques over the years that make a big difference to learners’ progress both inside and outside the classroom.

#1 have students read in class

This is so important. Many students lead busy lives, and reading in English will have a low priority. By giving them time to read in class, we ensure that all students are having the chance to spend at least some time engaged in this crucial activity. Additionally, if students start to read a book in class, the chances that they will then finish it after class increase dramatically.

#2 set achievable goals

Let’s face it, students rarely choose to read in English purely for pleasure. They may do it because they find it useful or because they believe it is a good way to learn, but most of them do so because their teacher asked them to. Finding achievable goals that push your students to read more and more without overburdening them is the key to a successful ER program.

#3 sell reading to your students

This is the foundation that the previous point rests on. It is essential that students understand why they are reading before they start. The principles of ER, guidelines and advice, as well as expected results should be made as clear to the students as possible. If students understand and, more importantly, believe in ER as a method, they are far more likely to succeed.

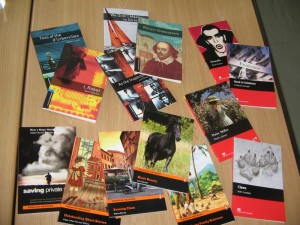

#4 recommend specific books

Introduce books to students based on their interests and your own. Hopefully you’ll have read all your readers and will be able to recommend specific books based on genre, level, length, and other factors. A personal recommendation makes it much more likely that students will read, and also more likely that they will find a book they like.

#5 give students time to talk about their reading

This may be the most important tip of all. Assuming that most of your students are participating actively in the program, you can harness the power of peer pressure and social proof. If students have time to talk to each other about the books they have been reading, they can share book recommendations and inspire each other to read more. Of course, if many of your students are not participating actively, you may wish to avoid this, as you run the risk of having them drag down the more active ones. It’s just a matter of reading your class to see if this would be beneficial or not.

So, what do you say? Any other good tips for running an ER class or program?